“I Was Completely Blindsided,” Parents Pushing for Action After Losing Children to Heart-Related Conditions

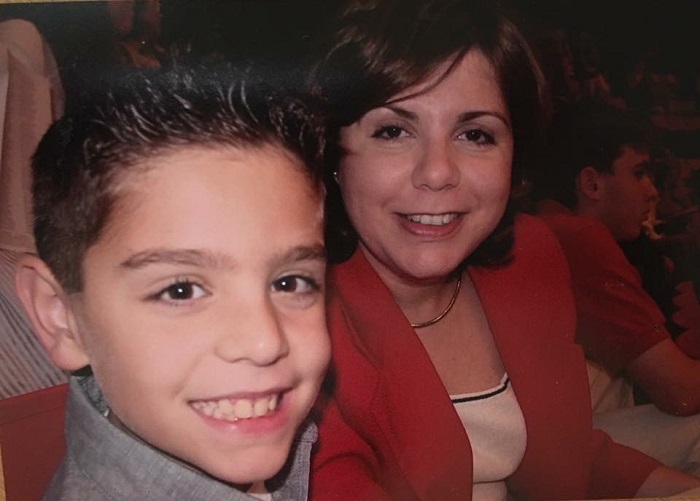

Sean Anderson was only 10-years-old when he died from sudden cardiac arrest.

To the outside world, Sean was a typical 10-year-old boy.

“He was a happy kid, loved sports,” Martha Lopez-Anderson, Sean’s mother, said.

Even though he was too young for most organized sports teams, he loved to rollerblade and play basketball with his friends.

Suddenly, he was gone.

In February of 2004, everything seemed perfect for the Anderson family.

Sean, who underwent a child wellness checkup a month earlier, seemed happy and healthy. On the day that would change their lives forever, Sean was rollerblading with friends and had even stopped by the house to grab a glass of water.

When Sean stopped in that day, Lopez-Anderson says Sean was laughing and joking with his buddies.

“He said, ‘Mom, closing the garage door. I love you,’” Lopez-Anderson remembers.

Sadly, those would be the last words he would ever say to her.

A short time later, Lopez-Anderson received a phone call from a neighbor. That’s when she learned that as he was rollerblading, he suddenly collapsed on the sidewalk.

“Obviously, that was not a good call,” she said.

Neighbors told her that they thought he was suffering from epilepsy because it looked like he was having a seizure. They had no idea that it was actually an issue with his heart.

By the time they realized it wasn’t a seizure, it was too late.

“How does a child that looks amazing collapse and die like that?” she asked.

His death came as a shock to the community, his friends and his family. About four and a half months after his death, family members learned that Sean died from sudden cardiac arrest.

“I was completely blindsided by sudden cardiac arrest,” Martha Lopez-Anderson told KFOR.

Not alone

Sadly, experts say deaths like Sean’s happen too often, and they are preventable.

In Missouri, Emma Aronson died after her heart stopped while swimming.

“She was racing in the pool against the boys and of course, she wanted to beat them. And most of the time she did,” said Laura Aronson, Emma’s mother. “She got to the edge and said, in a very small voice, ‘I’m so tired,’ and then that was it.”

Emma Aronson was just 17-years-old at the time of her death.

In Virginia, 16-year-old Cameron Gallagher died at the finish line of her first half-marathon.

The competitive swimmer seemed in good spirits until she became noticeably tired.

“A team of doctors tried everything they could to try and get her heart going again. Her heart had stopped and they just could not get it going back again,” said David Gallagher, Cameron’s father.

A case that may be familiar to some Oklahomans is that of 21-year-old Tyrek Coger.

Coger had just transferred to Oklahoma State University in 2016 and was rated as the 21st best junior college prospect in the nation.

He was on campus just two weeks before he died after a workout at Boone Pickens Stadium. The medical examiner determined that Coger died from an enlarged heart and an enlarged left ventricle.

Earlier this year, a 9-year-old Vinita girl lost consciousness at school after playing a game of basketball. She was rushed to a nearby hospital, where she died of an enlarged heart.

“Her heart was almost twice the size of a normal child’s heart,” said Amy Elliott, with the Oklahoma State Medical Examiner’s Office.

In addition to abnormalities with the structure of the heart, some people, like Sean, suffer from sudden cardiac arrest. Sudden cardiac arrest occurs because of an abnormality in the heart’s rhythm as a result of an issue with the heart’s electrical system.

What Can Be Done

While these deaths are rare, health experts say more can be done to prevent lives from being lost in a similar manner.

Dr. Kimberly Harmon was one of the authors of the ‘Incidence of Sudden Cardiac Death in National Collegiate Athletic Association Athletes.’ In the study, doctors looked at the deaths of 80 NCAA athletes and determined that cardiovascular-related sudden death was the leading cause of death in 45 of those cases.

The study urges athletic programs across the country to incorporate ECG screenings as a part of physicals for athletes.

According to the Mayo Clinic, an electrocardiogram, or ECG, records the electrical signals in your heart. It is a painless, noninvasive test that can help detect irregular heart rhythms and structural abnormalities in the heart.

“The European Society of Cardiology and the International Olympic Committee recommend an ECG as part of a preparticipation examination, whereas the American Heart Association has recommended only a history and physical examination, predominantly on the basis of concerns regarding cost-effectiveness and infrastructure,” the study states.

Harmon told News 4 that a standard sports physical or wellness exam is “unlikely to discover the underlying cardiac conditions that can lead to sudden cardiac death in young people.”

Instead, she says a simple ECG can identify about two-thirds of those at risk with a low false positive rate. She says the key is to have the test interpreted by someone familiar with the International Guidelines.

Although ECG’s are estimated to find 66 percent of silent cardiovascular diseases in athletes, not every school has added those tests to their physicals.

Oklahoma’s two largest universities, the University of Oklahoma and Oklahoma State University, have been performing ECGs on athletes for several years.

Not a perfect system

Even though ECGs can help prevent sudden death in athletes and children, it isn’t a perfect system.

According to officials at Oklahoma State University, ECGs were in use at the time of Tyrek Coger’s sudden death in 2016.

“OSU has performed/required EKGs (ECGs) for at least 10 years for all football and men’s basketball players. At the time of Tyrek Coger’s death, OSU was in the process of expanding that requirement to all athletes,” Carrie Hulsey-Greene, the associate director of communications for OSU, told KFOR in an email. “Although we can’t discuss individual athletes’ medical records, OSU protocol, at the time of Tyrek Coger’s death, would have required him to undergo an EKG (ECG) and echocardiogram in addition to providing an extensive personal and family medical history along with an exercise history and physical exam.”

Even though an ECG didn’t prevent Coger’s death, parents like Lopez-Anderson hope that a more widespread implementation of the tests could save the lives of others.

“ECGs are a good tool, but they are not perfect,” she said, adding that most health tests are not perfect 100 percent of the time. However, she says that doesn’t mean that we should stop using them.

Instead, she encourages families to know exactly who is reading the results and to push to make sure they are qualified.

“They need to know what they’re looking for,” she added.

Even though the tests can’t be right all of the time, some metro doctors say there is no harm in getting the test done, but warn that they may not be of much use if the child is asymptomatic.

Dr. Melinda Cail, with Primary Health Partners, says that ECGs are not invasive tests, so there is little danger associated with them. However, she says that there is usually no need to run the test on asymptomatic children.

“If a patient has a heart murmur identified on their annual check up or a sports physical, then it is definitely warranted. If there’s a history of sudden cardiac death in the teenage years in the family, then I think it would also be warranted,” Dr. Cail told News 4.

What parents can do

After Sean’s death, Lopez-Anderson realized there were thousands of other parents like her when she found ‘Parent Heart Watch.’

Today, the organization has more than 5,000 people in its database, who have all had their own experiences with sudden cardiac arrest.

In the past, the group sought to put automated external defibrillators in schools across the country. Now, the parents are pushing for better screenings and access to ECGs for all children.

“What’s happening today is not acceptable. Family history and a physical alone is failing our kids,” she said.

Lopez-Anderson, who is now the executive director of Parent Heart Watch, says they encourage parents to take a more proactive approach when it comes to their child’s heart health.

“Ask, don’t just assume your doctor is going to do this,” she said.

She encourages children to go through multiple screenings throughout their lives like at birth, when they start school, in middle school and in high school.

While the price tag can cause some families to raise eyebrows, she says it well worth it in the end.

“Parents are willing to spend a lot of money on video games, cell phones, Starbucks, but they’ll balk at spending a little money on checking their kid’s heart,” she said.

Lopez-Anderson says she hopes her story will shine a light on the importance of heart screenings.

In Sean’s case, he didn’t show any symptoms and never complained about chest pain.

“I always wonder if Sean felt something,” Lopez-Anderson said, adding that many children don’t know that what they are feeling isn’t normal.

Parent Heart Watch encourages families to have a productive dialogue with their kids, and to ask meaningful questions.

“Parents need to not just think because their kids look OK on the outside that they’re OK on the inside,” she said.

The group has even created a cardiac risk assessment to make it easier for parents to ask the right questions about their child’s health.

Potential warning signs include racing heart, heart palpitations, irregular heartbeat, dizziness, lightheadedness, fainting or seizure, chest pain or discomfort with exercise, excessive fatigue during or after exercise and excessive shortness of breath during exercise.

A lot has changed since Sean’s death in 2004, but many families say more needs to be done to bring awareness to the prevalence of heart conditions in children.

“Losing Sean changed my life and my family’s lives forever, but learning that his death could have been prevented is something I will never get over,” she said.

Story Credit: https://kfor.com/2018/08/27/heart-script/

Since you’re here, we have a small favor to ask. Requests from schools and districts for our screening services are growing, which means that the need for funds to cover the cost of those services is also growing. We want to make our services available to those who request it and beyond, so you can see why we need your help. Safebeat heart screenings take a lot of time, money, and hard work to produce but we do it because we understand the value of a child's life, PRICELESS!

If everyone who reads this likes it and helps fund it, our future would be more secure. For as little as $1, you can support Safebeat and it only takes a minute. Make a contribution. -The SafeBeat Team