‘Some Things You Don’t See Coming’: Florida’s Randy Russell Talks Heart Diagnosis, Not Playing Football

Florida signee Randy Russell was found to have a heart condition that prevents him from playing for the Gators.

GAINESVILLE, Fla. — Keisha Carnegie-Russell was at work when she got the call from Florida’s head athletic trainer, Paul Silvestri, in mid-January. The very next day, she was on her way to Gainesville, but she couldn’t tell her son she was coming — or why.

He needed to hear this in person.

“It was hard. It was really hard, but it was important for me to be there when he got the news,” Carnegie-Russell recalls months later.

Randy Russell, an intriguing safety prospect and early enrollee for the Gators, hadn’t been on campus long when the first indication came that something might be wrong.

The standard medical exam given to all the incoming freshmen football players revealed a potential issue with his heart, but nothing could be diagnosed until Russell underwent further tests. As Russell recounts, the echocardiogram showed that his heart was enlarged and he’d have to undergo a further cardiac MRI to better identify the issue.

He had never felt any different, though, nor did he feel anything was out of the ordinary this time, either.

“I didn’t know anything possibly they could be looking for, but I wasn’t expecting it because I’ve been healthy all my life,” Russell says.

Silvestri was calling to tell Russell’s mother that the cardiologist had diagnosed her son with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (or HCM), a condition in which the heart muscle becomes abnormally thick, making it hard for the heart to pump blood.

And that it meant he wouldn’t be cleared to play football for the Gators.

She brought Russell’s girlfriend with her to Gainesville and they met in coach Dan Mullen’s office along with Silvestri and Dr. Jay Clugston.

“Coach Mullen was there, my mom was there — I didn’t know she was here, but she came up — and I walked in and I pretty much seen her face and that’s when I knew,” Russell recalls, sitting inside The Swamp a week and a half ago. “That was pretty much the last thing on my mind, being that I never really experienced any problems.”

It was a difficult gathering.

“It wasn’t easy for anyone in that room, the team doctor, it wasn’t easy,” Carnegie-Russell says. “[Randy] just broke down and cried. It was more of a ‘Why me, why me?’ We really did not see this coming. Some things you don’t see coming. This we did not see.”

How could they, after more than a decade of playing football, of being intently focused on this goal and seeing it through all the way to a coveted opportunity now at the SEC level? An opportunity that was suddenly being taken away.

More than three months since the day that Russell’s world changed, Jan. 11, he’s admittedly still processing everything.

He still chooses to believe that his faith in God will lead to a solution that gets him back on the field one day, even if there is nothing medically to indicate the situation can improve or be reversed.

Russell is doing better than he was, he says, but there are still days he offers up a feigned “I’m fine” when people inquire. There are days when he just doesn’t want to talk, even with his mother on their daily call.

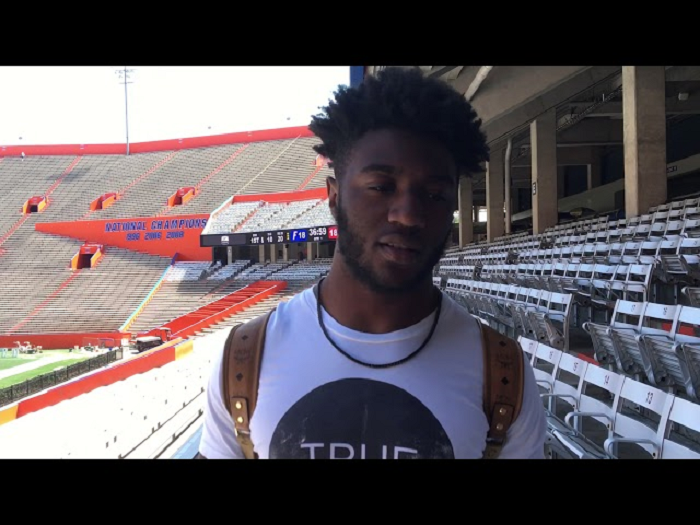

On this day, though, two days before Florida’s Orange & Blue spring game, two days before he’d watch his teammates take the field before 53,000 fans, Russell sat inside a mostly empty Ben Hill Griffin Stadium and opened up on what he’s been through and how he looks at the future.

“Those were probably like the worst days of my life. Probably the worst month. It was just tough. At times I didn’t want to wake up out of bed,” Russell says of the initial shock. “Still, to do this day, I’m still trying to piece everything together. It’s still hard for me.

“But I’m a firm believer in God, that he works in mysterious ways,” he continues. “And to this day, I still have faith. I still believe that one day it will all, the sickness will go away and I’ll end up playing again. But like I said, I’m still piecing everything [together] and taking it one day at a time because everything is not in my hands.

“I just leave everything in God’s hands.”

The path to Florida

A few months earlier, in late December, Russell and his mother sat in the family’s living room in Miami Gardens, Fla., having a much different conversation.

About how Russell first signed up for football when he was 4 or 5 years old, how he impressed his youth coaches with unusual maturity and focus for his age, how he had done everything in his power to will this goal into reality.

No matter the obstacle.

“Schools like Alabama, LSU, they were scared to offer me because of my physique. I guess I wasn’t big enough or tall enough. Things like that motivated me. … I’ll show you why you should have offered me,” Russell said then.

When he signed with Florida, he was rated a 3-star recruit and ranked the No. 28 safety in the Class of 2018, according to the 247Sports composite. The Gators listed him at 5-foot-10, 176 pounds.

Even new Gators defensive coordinator Todd Grantham told Russell he didn’t fit the prototypical frame he looked for in safeties, but there was something about the way he played the game that superseded any such hesitation.

“He said he didn’t care how tall I was or how big I was. He said he knew what kind of player I was, and what I would be capable of,” Russell recalled shortly after making his pledge to Florida official during the NCAA’s early signing period.

Sitting in the family’s living room in late December, Leon Trimble recounted the notable players he coached at the youth level over the years — future NFL star wide receivers Antonio Brown and T.Y. Hilton, fellow NFL wide receiver Tommy Streeter and former FIU and NFL cornerback Anthony Gaitor.

And then he shared what set Russell apart from all of them in his eyes.

“Randy’s character is like no other kid I ever been involved with, and I’ve been involved with the greats,” said Trimble, who started working with Russell when he was 8 or 9, as the defensive coordinator on the Northside Optimist Club team.

“Randy’s character at 8 and 9 years old was like a fifth-year senior and a grown man at a university. His IQ level for the game, he picked up things like this. And he’s in the same category as those kids. … But something special about Randy that they didn’t have, Randy has a special character. He’s like a sponge. … I knew then he was special.”

While Trimble rattled off his assessment, Russell sat taking it all in, nodding a little as he listened.

He did have an unwavering focus for football, and he saw first hand how that differed from some of his peers. As time went on, he says he’d separate himself from those on a different path.

“A lot of past teammates, they’re not playing football anymore because they either got caught up with things, going to jail, getting shot, dying, things like that,” Russell said at the time. “I use that as a teaching tool for myself to stay focused because things could easily go left. … I just look at the bigger picture.”

His mother chimed in, noting how Russell was always either playing football, at the gym, at his girlfriend’s house or at home.

“I know what I want. I’m good with that life,” Russell said.

Trimble continued on talking about Russell’s football abilities, the versatile ways a coaching staff could use him, how quickly he picked up things and needed to be told only once, etc.

But he always came back to one thing above all else.

“I know that Randy can go as far as Randy wants to go because of Randy’s character,” Trimble says. “… Randy is like no other kid. He was like a grown man when he was 8 or 9 years old.”

“There’s a lot in him just waiting to go to that level and the level after that. I see big things in Randy,” Trimble added.

Russell’s mother laughed as his youth coach added sound effects for what it was going to be like once the Gators fully unleashed him on the field.

He was set to move to campus in the next couple weeks, and his steely focus didn’t relent during that hour in his home, as his mother and old football coach told stories about him and as he talked about his future.

“I just look at it as there’s still more to go. I’m halfway there, I just have to finish what I started,” Russell said then.

Finding perspective

Just as his mother recalls vividly the moment she got that call from Silvestri, Florida’s associate director of sports health, Russell remembers right where he was for another unexpected phone call.

This one came from Cooper Manning, brother of NFL quarterbacks Peyton and Eli Manning and a high-profile wide receiver recruit to Ole Miss before a diagnosis of spinal stenosis ended his college football career before it began.

Few could relate to what Russell was going through, having his life change in an instant, but Manning could.

“He reached out to me while I was in class, but I didn’t recognize the number. I knew it had to be somebody important,” says Russell, who stepped out of class to see who was calling. “I ended up answering it and he told me who he was, and I was in shock. But we talked for about almost half an hour. We just vented to each other, and ever since then we’ve just been in constant contact.

“We’ll text every now and then, he’ll call me and check up on me, I’ll do vice versa. Things like that. Whenever I’m feeling down or need some advice, I’ll call him.”

In the aftermath of the diagnosis, Russell’s mother would receive some impactful calls as well, including one from a woman named Michelle Fields-Wilson, whose son Nick Blakely died of sudden cardiac arrest last summer before his sophomore season at Stetson after feeling dizzy at practice and later collapsing.

“We couldn’t believe that he had come this far for something like this to happen, but looking at the big picture I’m just grateful they were able to find it out now sooner than later, a worst-case scenario of something happening for him,” Carnegie-Russell says.

Russell echoes that sentiment, though it doesn’t make this any easier.

“There’s always a positive because at the end of the day it could be 10 times worse,” he says. “… Any time you can prevent anything like that from happening, it’s always a blessing, but at the end of the day I still wish I was playing.”

Russell says a lot of people tell him he doesn’t seem himself anymore, that he’s missing the “glow” he once had.

“I can see why they would say that. I hope one day I’ll get it back,” he says.

In the meantime, he’s stayed close to the sport he loves and the team he was so excited to join.

Florida told Russell they would honor his scholarship, and Mullen encouraged him to remain involved with the program to whatever degree he wanted. Both Russell and his mother laud the way Mullen has treated him since the diagnosis.

And it’s not a surprise to those who know Russell that he’s chosen to fully immerse himself in everything the Gators do, even though he can’t be physically involved.

“All practices, all meetings, I’m always around,” he says. “I still believe that I’m a part of the team, and everybody else seems to believe so as well.”

Russell lives with Florida wide receivers Trevon Grimes and Kadarius Toney and says he’s grateful to remain so involved with the Gators.

But he does have more free time on his hands than some of his teammates.

So after being undecided in December whether he wanted to pursue law or medicine at Florida, he’s chosen to pursue pre-med and has already spent about 40 hours shadowing Dr. Nicholas Cassisi at UF’s Shands Hospital.

His mother feels that maturity Russell’s youth football coach spoke so much about back in December is what has helped him through these last few months and what has helped him begin to consider an alternate path from the football dreams he admittedly still carries.

“When it’s all said and done, he’s going to be somebody. Whether it’s a football coach, doctor, lawyer, you haven’t seen or heard the last of him,” she says. “I don’t know what God’s plan is for him. He has a plan for him.”

Sitting in the stadium last week, Russell was optimistic that the results of wearing a heart monitor would allow him to return to working out again.

It would be at least a step back to normalcy.

His mother mentions there is also a decision to make as to whether he gets an implanted defibrillator down the road. “It’s his decision,” she says, noting that doing so would be formally accepting that he was officially done with football.

She acknowledges, though, that the doctors have not talked to him about the potential of playing again regardless.

Russell’s condition, HCM, is the same shared by former Loyola Marymount basketball star Hank Gathers, who collapsed during a game in 1990 and died shortly thereafter. The condition can be managed throughout life, but vigorous physical activity can trigger sudden cardiac arrest in rare cases, according to the American Heart Association.

Russell’s mother knows how much football still means to him, though, so she shares his optimism and his faith.

“I still have hope. I really believe he’s going to play again. I feel like everything happens for a reason,” Carnegie-Russell says. “I don’t know, I can’t really say, but I just have a feeling like I can’t believe he has put so much work and effort into football and not be able to play. Even if it’s just for one season, I just believe he’s going to play a little.”

For his part, Russell says he too knows what the medical opinion would be and he does not discuss with his doctor his hopes for a return to the field.

“I just keep it to myself. It stays between me and God,” he says.

Football has been his dream and he’s not letting it go.

“Never,” he says.

But as his mother said, spend some time with Russell and it’s easy to share the conclusion that he’ll make the most of whatever lay ahead.

“My future’s anything I want it to be,” he says. “That’s what I set my mind to do. Anything I want to be, that’s what I’m going to do.”

Story Credit: https://www.seccountry.com/florida/florida-gators-football-randy-russell-heart-condition-future